K’ómoks First Nation Origin Stories

KFN today consists of several formerly separate tribes, both culturally K’ómoks and Pentlatch. The Sathloot (‘sath-loot), Sasitla (sa-‘seet-la), Ieeksen (eye-‘ick-sun) and Xa’xe (‘ha-hey) are all culturally K’ómoks and have their own unique origin stories. The Pentlatch had a similar culture but spoke a distinct language and also have their own unique origin story. These origin stories all tie the tribes’ first ancestors to their respective tribal territories.

We have included a selection of KFN origin stories below, and will continue adding others as we are ready to share.

A Sathloot Origin Story

A long time ago, Cia’tlk’am (‘shal-kum) descended from the sky. He wore the feather garment Qua’eqoe (‘khwhy-khwhy) and settled in Nga’icam (Quinsam). He became the ancestor of the Catloltq (Sathloot). With him, his sister Te’sitla (teh-‘seet-la) arrived. She was so big that she needed two boats to cross the sea. The brother and sister wandered through all countries and visited the Nanaimo…

A Pentlatch Origin Story

A long time ago, two men, Koai’min (‘koh-yuh-min) and He’k’ten (‘heck-oo-tin) descended from the sky. They became the ancestors of the PE’ntlatc (Pentlatch). Once the sea receded far from its shore and the women went out far and filled their baskets with fish. The bottom of the sea remained dry for a long time. But He’k’ten was afraid that the water would rise that much higher later on…

Another Pentlatch Origin Story

In the beginning, long ago, there were no people living at Punt-Lutz. Then, a long way back in the woods where there was a lake, a man was made. For a long time he lived there alone eating the roots that he found, and after a time, he woke up, and he saw a woman standing looking at him. She was a fine, tall woman, with long hair that reached right down to her feet; but she had no arms. The man jumped up and ran to catch her…

K’ómoks First Nation History

K’ómoks First Nation’s history begins with the arrival of their ancestors to this territory at the end of the last Ice Age. Descent from these First Ancestors tie the K’ómoks and Pentlatch tribes to their respective territories. For thousands of years, KFN ancestors occupied the extent of their territories, and harvested and managed the rich natural resources therein. These lands and waters supported thousands of people who developed a rich and sophisticated culture. The disease and warfare that accompanied contact with Europeans in the late 18th century decimated KFN ancestors, just before an onslaught of settlers came to their territories. From this time, KFN has struggled against colonial policies that tried to alienate KFN people from their territories, resources, and culture. Despite all of this, KFN’s ancestors persevered, and current generations of KFN people continue to assert their rights and title to the whole of their territory.

K’ómoks People History

K’ómoks First Nation, like many First Nations, is composed of culturally related, but distinct groups or tribes, that, through various historical processes have come to be organized together as a single modern First Nation. The organization now known as K’ómoks was first recognized by Canada as a distinct Indian Band in 1876, with the formalization of the Comox Indian Band.

The K’ómoks History was prepared by Jesse Morin, PhD, Archaeologist, Ethnohistorian, Heritage Consultant, Adjunct Professor at the SFU Department of Archaeology, and Adjunct Professor at the UBC Institute for Oceans and Fisheries.

Read below for a Summary of the K’ómoks History.

Our Languages

tuwa akʷs χoχoɬ ʔa xʷ yiχmɛtɛt (ʔa) kʷʊms hɛhaw tʊms gɩǰɛ

“Care takers of the ‘land of plenty’ since time immemorial”

(Language: Ayajuthem (eye-uhh-juu-eth-em))

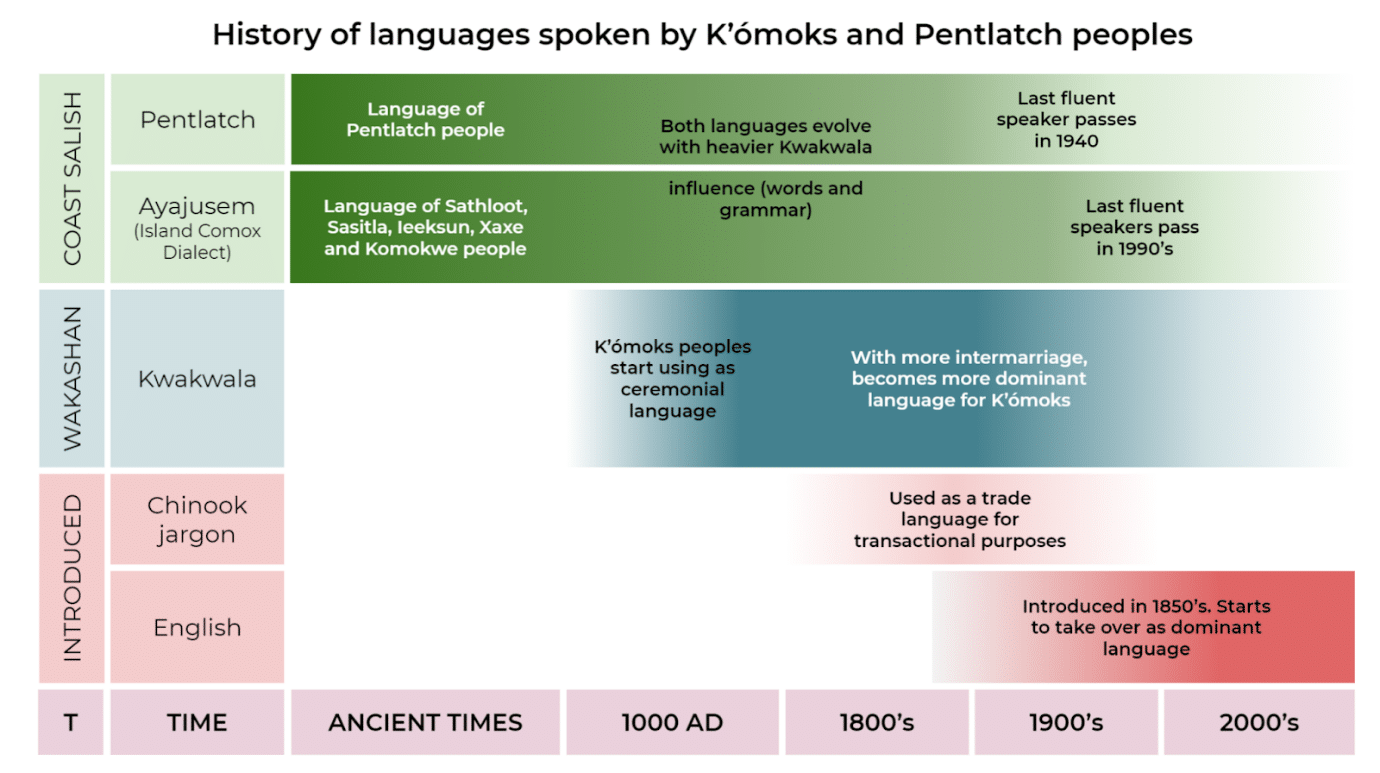

The K’ómoks First Nation is proud to be a part of two dominant cultures, Northern Coast Salish as well as Kwakwaka’wakw. Historically, our ancestors spoke Pentlatch or ayajusem (Island Comox dialect). They would also have been familiar with a number of neighbouring languages such as Kwak̓wala, given extensive trade and intermarriage. Their language use was complex, and evolved over time.

Language Revitalization Efforts

K’ómoks First Nation and its members are undertaking the huge task of language revitalization, and several classes are offered for both ayajuthem and Kwak̓wala. KFN is inclusive of all of our cultures.

Kwak̓wala: through the revitalization of our Northern Coast Salish roots and celebration of Kwakwaka’wakw culture, we are rebuilding our unique K’ómoks culture. Kwak̓wala has been the most accessible language for K’ómoks to celebrate, it being used in potlatches and for other ceremonial purposes.

In addition, Kumugwe Cultural Society (a K’ómoks member led society) is doing a Kwak̓wala language revitalization project, Wiga’xa̱n’s Yaḵ̓a̱nt̓alape, which is going into its second year as of 2021.

Ayajusem: K’ómoks has a few language warriors who are working towards bringing back the Island Comox Dialect, ayajusem. The K’ómoks First Nation Cultural Coordinator has been working closely with our sister nations, Homalco, Tla’amin, and Klahoose, who share the same traditional language, ayajuthem (Mainland Comox Dialect). We are collaborating as a working group to find a way that we can all share in language and cultural teachings between our nations, and determine how we can best share this information with our communities.

Pentlatch: in recognition of our Pentlatch ancestry, we have worked closely with a professional linguist to reconstruct a Pentlatch blessing to be used in cultural work.